About this blog

Three months off retiring, I was asked if I had thought of Jerusalem. I resisted the temptation to reply that I thought of Jerusalem on the hour every hour. Instead, I asked: Had I thought what of Jerusalem?[1]

And behold, it came to pass that, after a certain amount of Church of Scotland process, I found myself from 2014 to 2018 as minister of St Andrew’s Scots Memorial Church, separated from the Jaffa Gate by the valley of Hinnom (that’s Gehenna, to you).

Engaging with Christians, Jews and Muslims in a strife-torn land, I reflected that this was obviously some strange usage of the word retirement I wasn’t previously aware of. But eventually it was time to return to the serenity of rural Switzerland, where the livin’ was easy. Until the coronavirus struck.

This blog is after Jerusalem in that sense. But it’s not all about me, and not even all about the strife (although often it will be).

Two thousand years ago, the Jesus movement, beginning from Jerusalem, ramified through all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.[2]

The universal church of Jesus Christ is also after Jerusalem; and this blog will be after Jerusalem in that sense too.

Readers, if any, are entitled to know where I’m coming from, so let me confess that I am committed to an understanding of Christianity that is biblically critical, doctrinally conservative, liturgically sensitive, socially liberal, and politically radical. These are, of course, mere labels, and labels may mislead. What they mean concretely should become clear in the course of the blogging, if you haven’t already left…

I owe my title to James Thurber, courtesy of my late friend and mentor Laurence Bright OP.

In 1970, Laurence and I attended a workshop of the European region of the World Student Christian Federation in Lund, Sweden. We wrestled with how to relate the languages of religion and politics – or more concretely, as some of us saw it, Christianity and Marxism. We didn’t get very far.

Later, Laurence wrote a reflection on the meeting, entitled “After Lund, what?” When he saw I missed the allusion, he asked in mild astonishment, “You’ve never read James Thurber’s After the Steppe Cat, What?”

I have now.

So I dedicate this blog to the memory of James and Laurence, recognizing my debts to the theology of the one and the humour of the other.

Or the other way round, of course.

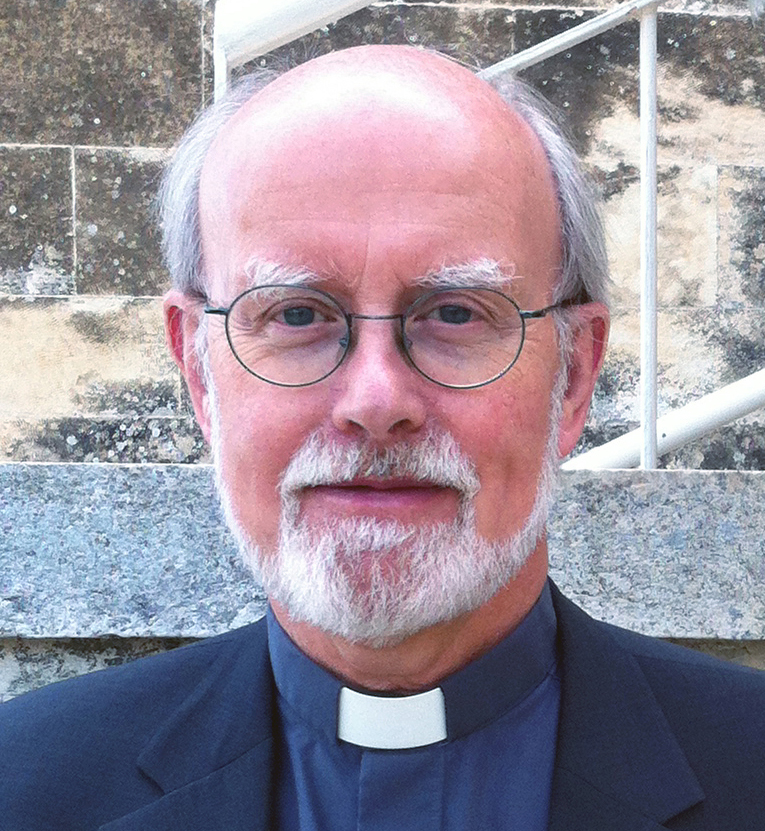

About its author

Páraic Réamonn was born and bred an Irish Catholic and became a minister in the Church of Scotland thanks to Vatican II. (After a single malt, he’ll explain that.)

He went to University College Dublin aged 17 to study mathematics but, following an existential crisis, switched to philosophy, which didn’t resolve it.

In the Milltown Institute of Theology and Philosophy, Dublin, he briefly taught epistemology in the non-academic stream (his life is full of such contradictions).

He moved to Edinburgh in 1972 to work for the Student Christian Movement and liked Scotland so much he stayed. From 1982 to 1993, he was minister of the linked charge of Cockburnspath, Innerwick and Oldhamstocks, straddling the East Lothian/Berwickshire border. On his departure, this became the parish of Dunglass – the only Church of Scotland parish, he says, named after a quilt group. (After a second single malt, he’ll explain that too.)

In 1993, he moved to Geneva, Switzerland, to work for the World Alliance (now Communion) of Reformed Churches (WARC/WCRC). While there, he also worked in communication for the International Union against Cancer (UICC), now more coherently the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), and for Globethics.net.

From 2014 to 2018, he was minister of St Andrew’s Scots Memorial Church, Jerusalem.

He is now a backseat driver in the Church of Scotland, Geneva, which worships in the Auditoire de Calvin when there isn’t a pandemic.

He has three sons by his first marriage and a wife by his second.

Disclaimer

Nothing I say on this blog may be taken as speaking for the Church of Scotland. Only our general assembly does that.

This gives me the freedom to say what I think – and the Kirk the freedom to say, “Please, God, it wasn’t me, it was him.”

[1] The first Irish commandment: Always answer a question with a question.

[2] Luke 24.47; Acts 1.8.